Nicola Ranger, Director of Climate and Environmental Analytics, CGFI

Rowan Douglas, Insurance Development Forum and Head of Climate and Resilience Hub, WTW

Jim Hall, Professor of Climate and Environmental Risk, Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford

Jenty Kirsch-Wood, Head of Global Risk Management and Reporting, UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction

Nick Moody, Insurance Development Forum and Private Sector Head of the Global Risk Modelling Alliance

On adaptation finance, we are going in the wrong direction.

Recent crises clearly demonstrate the urgency of investing in resilience, yet the adaptation finance gap is widening and risks are accumulating far faster than finances are growing. The 2022 UNEP Adaptation Gap report estimated the adaptation finance gap to be five to 10 times greater than current international adaptation finance flows.

Taking into account wider financial flows, there is evidence that we are going in the wrong direction. For example, the 2022 TCFD Status Report found that physical risks are under-priced in financial markets. The $3 trillion per year invested in infrastructure is more than 60 times larger than all tracked climate finance for adaptation, yet in many parts of the world, infrastructure does not meet minimum standards.

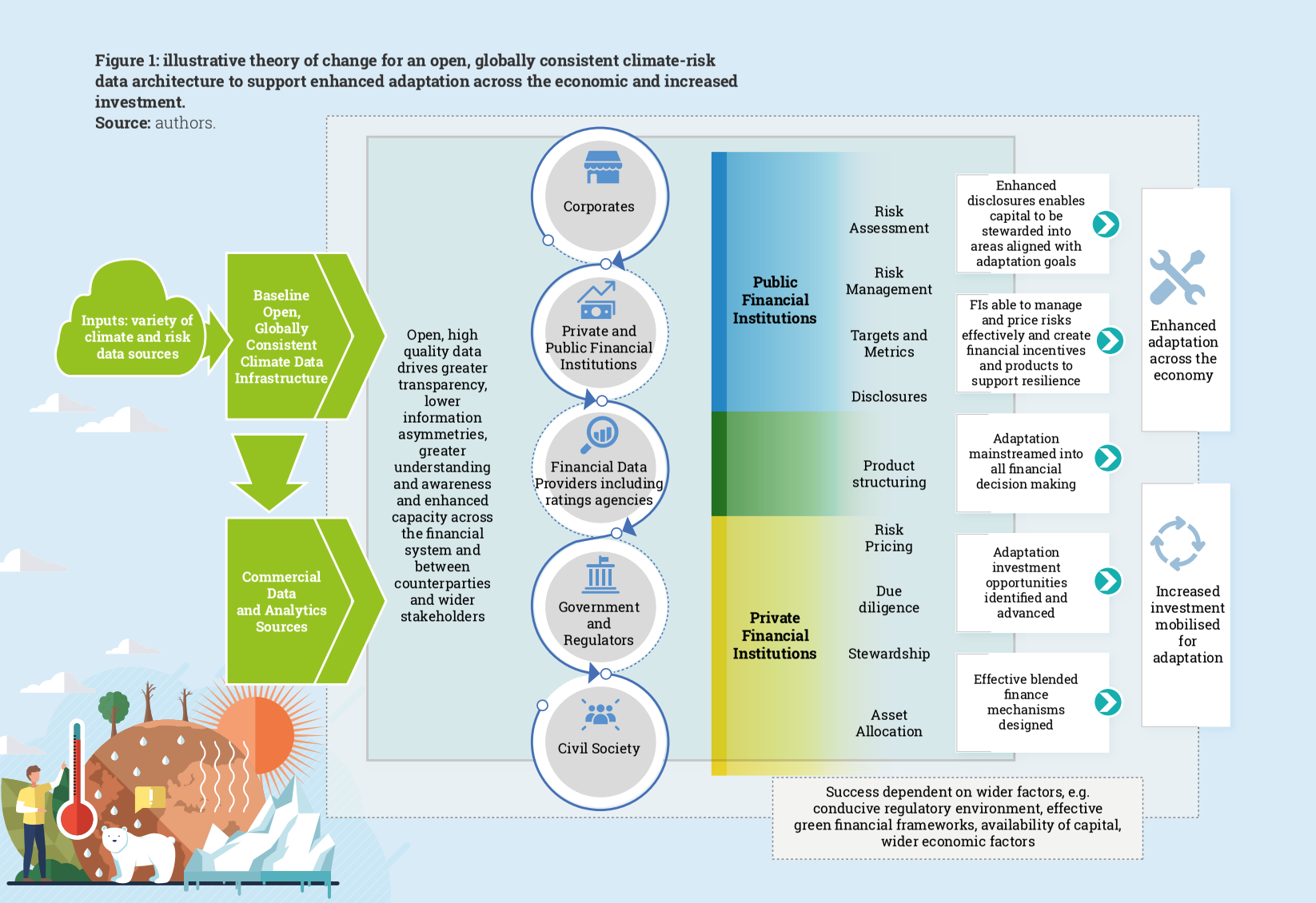

As a foundation to scale up investment in adaptation, organisations including the International Monetary Fund (IMF), United Nations, V20 Group of Ministers of Finance, Global Centre for Adaptation and the Taskforce for Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) have called for improved climate risk information and a shared climate risk data architecture – that is, a common ‘language’ of climate risk.

Why is this common language for adaptation financing so important?

For contrast, look at net zero data, where the common metric of tons of carbon means that a shared understanding is in place from local to global level. Upon this, we can set measurable and verifiable targets, design policies, develop markets and products, compare investment opportunities and align capital flows with the Paris Agreement.

This same does not yet exist for adaptation, and action is accordingly limited. This needs to change.

Limited information, limited adaptation

Today, high quality information tends to be accessible only to those who can afford it. Even then, there is a lack of transparency over methods, inconsistencies across datasets and an incomplete representation of the risks.

We have no consistent, comparable, baseline metrics for risk and resilience. This means

that risks cannot be consistently priced. Two investments cannot be robustly compared. And verifiable targets are difficult to set. Mobilising investment and aligning financial flows with climate-resilient development goals – Article 2.1c of the Paris Agreement – consequently becomes much more challenging.

As explained by the IMF, strengthening the climate information architecture is paramount to promote transparency and global comparability of data. This in turn will improve market confidence, safeguard financial stability, and foster sustainable finance.

Similarly, the TCFD promotes a common approach to measuring and valuing risk which, when coupled with disclosure, ensures that different firms, assets or investments can be compared on a level playing field. Risk pricing can then act as an incentive for investing in resilience.

This transparency in risk creates the discipline essential to support improved alignment with societal goals. It also unlocks the potential for new types of financial products for adaptation, including sustainability-linked bonds and loans for resilience, resilience-index linked funds or debt-for-resilience swaps to mobilise investment.

The UN Disaster Office for Disaster Risk Reduction tell us that this new ‘risk language’ must cut across sectors to break down asymmetries in understanding of risk across society. It must level the playing field across governments, civil society and financial institutions.

The bottom line is: if we want to truly reach the scale of adaptation finance needed, we need to create a common language that will allow finance to understand then respond to the risks.

Levelling the playing field with open climate risk data

At COP26, a new taskforce set out to try to bring together the best of open climate risk data, and fill the gaps to create a prototype common language. The Global Resilience Index Initiative (GRII) was founded by six partner collaboratives, convened by the Insurance Development Forum under mandate provided by Mark Carney, UN Special Envoy for Climate Action.

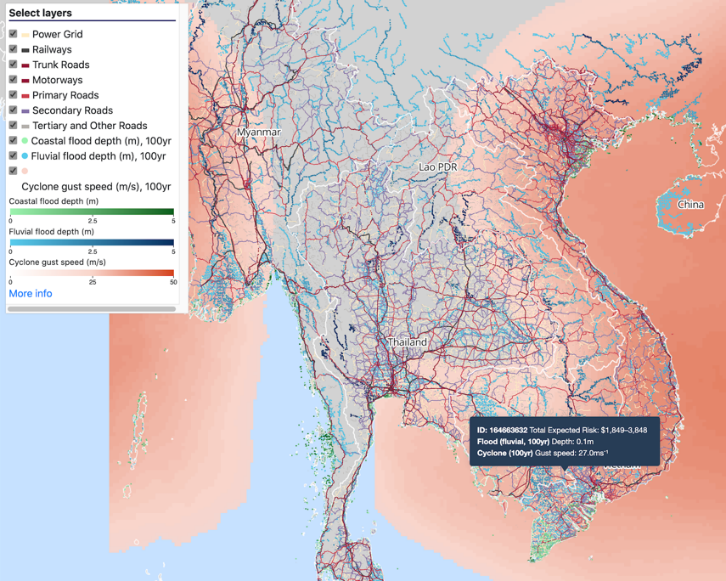

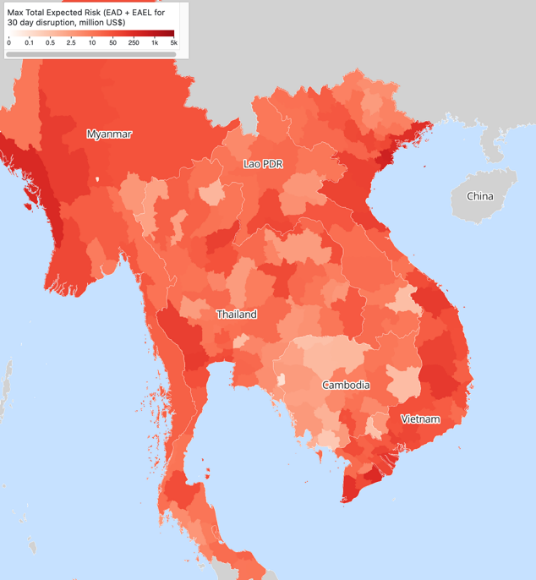

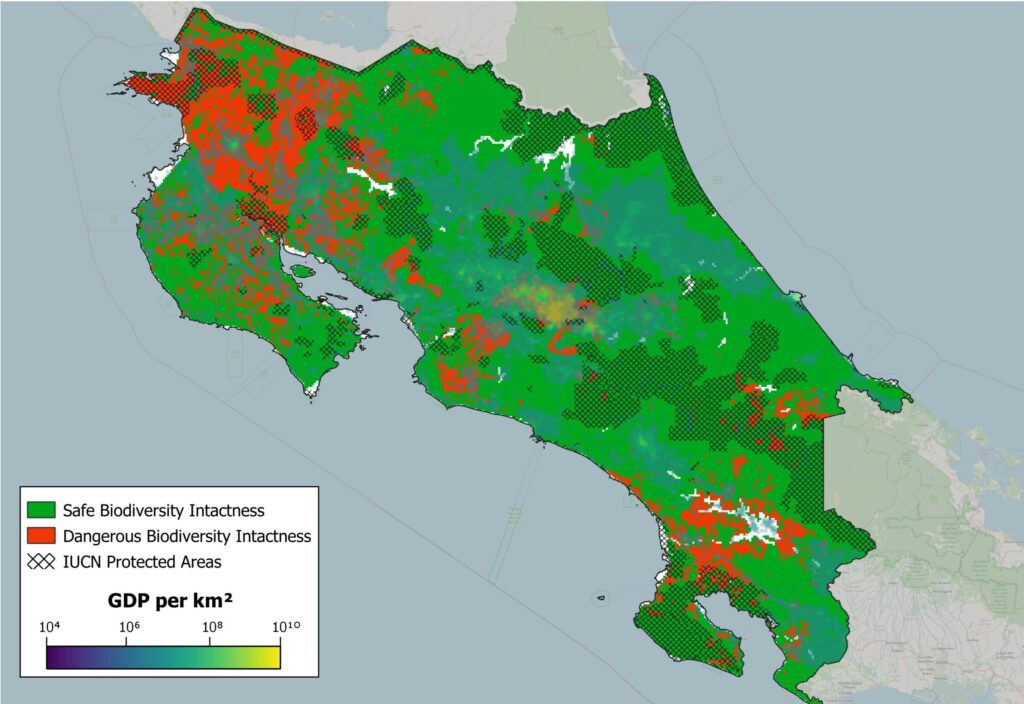

GRII is an open collaborative initiative, rather than just a data product. Unlike standard physical risk indices, GRII provides both asset-level and sub-national data, fully transparent and open, based on catastrophe risk modelling approaches of the insurance industry, coupled with best-in-class environmental science and engineering. It takes a people-planet-prosperity approach, including data and models of nature, biodiversity and social vulnerability factors, alongside built environment, infrastructure, economic activities and economic systems.

Over the past year, the taskforce has consulted widely and developed a roadmap for a baseline climate risk data architecture. The findings are outlined in a report launched this week jointly by two of the founding institutions – the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) and the UK Centre for Greening Finance and Investment.

The report highlights how asset owners, banks, central banks, infrastructure financiers, asset managers, ratings agencies, insurers and professional service providers all need– and can benefit from – an open, globally consistent, baseline dataset. Importantly, it finds that this architecture does more than just level the playing field and reduce information asymmetries; it can also raise quality standards and transparency across the whole data ecosystem.

Open climate risk data is not a replacement for commercial solutions, but instead complements the wider ecosystem as a public good to address important market failures, increase demand for information, and accelerate progress across data providers.

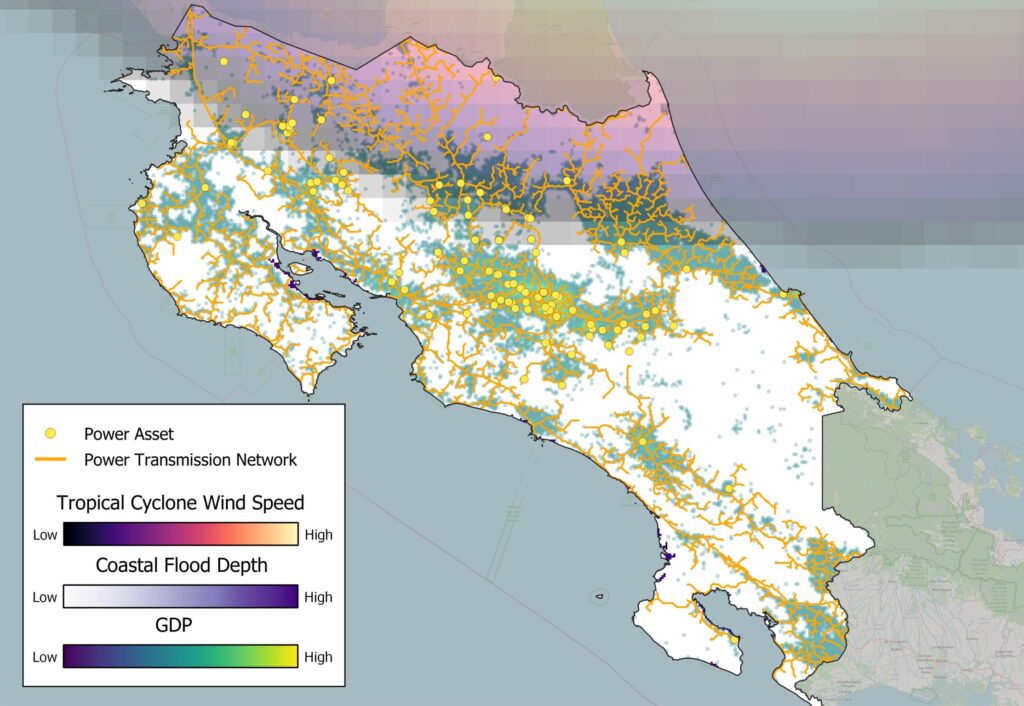

Initial user testing with both public and private users, including in Costa Rica, has informed the development of the GRII Global Systemic Risk Assessment Tool (G-SRAT), led by the University of Oxford, and launched on Adaptation Day at COP27.

Mapping asset exposure to flooding and cyclones in Costa Rica (left) and biodiversity loss (right). Source: Oxford Sustainable Finance Group.

Now, the GRII taskforce is announcing a challenge to businesses, governments and leaders. Mami Mizutori, Assistant Secretary-General and Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Disaster Risk Reduction in the UNDRR, and Patron of the GRII said:

“This project has only just begun and to reach its full potential, the GRII needs more data feeds, and more pathfinder institutions and governments.

At COP27, I am calling for Zero Climate Disasters by 2030. If we double down on efforts to reduce vulnerability, poverty and inequality, I believe this can be achieved. Quality risk data will play a crucial role in this. We need data that is comparable across all continents – on hazard, exposure, vulnerability and climate change risk.

GRII is an excellent example of private and public sector partners working together to reduce disaster risk. We must now accelerate systemic data collection and aggregation for risk-informed climate action.”

Investing in systematic data collection and aggregation to enable quality data that is comparable across all continents with regards to hazard, exposure, vulnerability and climate change risk is a global common good with significant benefit to all stakeholders across the public and private sectors. GRII is just the start – a demonstrator of what is possible and a nucleus upon which to build.

At COP27 and beyond, the world now needs to come together to build the common language of risk.